These days, the crusades are so commonplace that it’s difficult to imagine anyone ever forgetting about them. People play video games like Crusader Kings II and Assassin’s Creed (which features the Templars) in droves, and newspapers are flooded with pictures of young men marching in cities like Charlottesville while carrying shields emblazoned with the old crusader motto “Deus vult” (God wills it! ), and every year dozens of books about the crusades are released, informing readers about the most recent advances in crusaders history. And the information these books provide from the research front lines may come as a bit of a shock to our systems that have been saturated with the crusades: According to several historians, the Islamic world showed little to no interest in the crusades against Islam for the longest time. These experts challenge us to envision a world in which memories of the Christian holy war had all but disappeared at a time when echoes of the Crusades are pervasive.

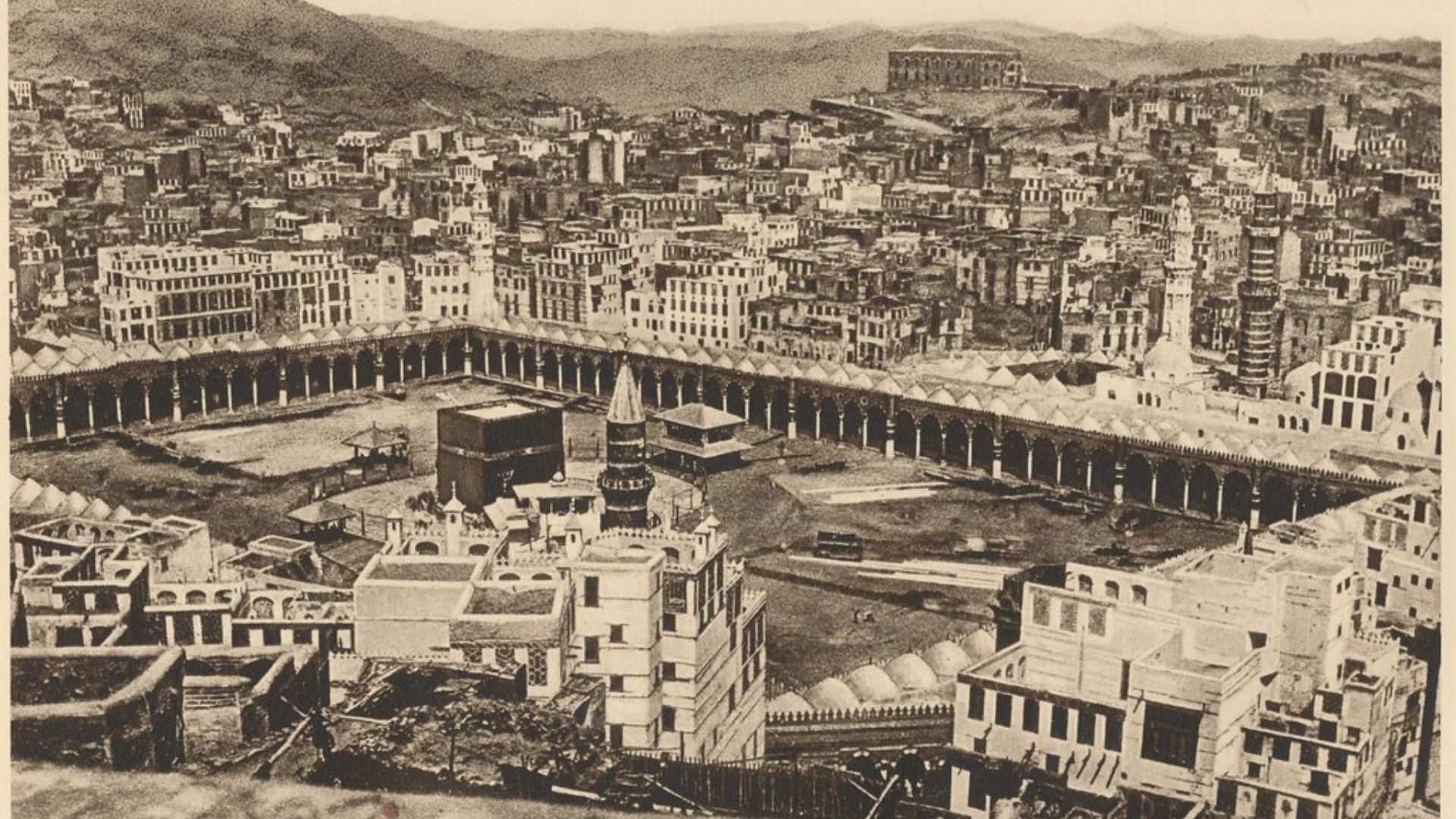

How could Muslims have forgotten the 200 years of conflicts they fought with Christians in medieval Latin? The Crusaders never succeeded in becoming much more than a bother to the Muslim powers of the day—first the Seljuk empire and then the Great Mamluk sultans of Egypt—whose real ambitions (and thus rivals) lay elsewhere. This is true even though the initial conquest of Jerusalem in 1099 came as a shock. The crusades against Islamic rule could be easily forgotten once the last crusader bastion of Acre fell in 1291, with Ottoman triumphs in the Balkans now taking the main stage. In any case, it was thought that Muslims had never really been interested in the world outside of Islam.

While what is frequently referred to as the first chronicle of the crusades against islam written in Arabic by a Muslim (Sayyid Ali Hariri’s Book of the Splendid Stories of the Cross Wars) emerged in 1899, the Arabic title for the Crusades—hurub al-Salibiya, or “Cross Wars”—was not adopted until the mid-19th century. By then, Muslims were starting to remember their prior interactions with their Western neighbors thanks to the subtle nudging of the European empire. Therefore, the “long memory” of the crusades in the Muslim world is actually a created memory—one in which the recollection is far younger than the event itself—according to a well-known crusades textbook currently frequently offered in US colleges.

We need to think about the repercussions when crusade historians instruct undergrads that contemporary Muslim memories of crusader atrocities are mainly fake. The message about Muslim curiosities is loud and plain here: pre-modern Muslims were reportedly so cut off from Europe that they could forget about the crusades against Islam for long periods. The argument presented regarding the legacy of the Latin Christian holy war is much more contentious. Muslims cannot be held responsible for igniting current hostilities because they were able to forget the Crusades against Islam, which suggests that they did not cause much long-term harm.

Regardless of the implications, if this assertion is true, it is true. That is the way the study of history must proceed. The issue is that, given the current state of affairs, the claim that “Muslims forgot about the whole thing anyway” is a thesis devoid of supporting data. Although most Crusades historians are fluent in the pertinent European tongues, they rarely consult Arabic or Ottoman Turkish sources. As a result, the study that could establish this widespread case of Muslim amnesia—looking for allusions to the crusades among the hundreds of histories, geographies, biographical dictionaries, travel accounts, inscriptions, and poems—has not yet been completed.

Even a cursory look through Arabic texts yields intriguing hints of a more complicated Muslim interaction with crusading. Ibn Khaldun, a scholar from North Africa, described a sequence of conflicts between Latin Christians and Muslims that lasted for centuries and took place in North Africa and the Near East until being won by the Muslims. He didn’t employ the phrase hurub al-Salibiya in its contemporary form, but why would he? He was a 14th-century man, not a contemporary. Shaykh Muhammad al-Alami resided in 17th-century Jerusalem, which is thought to have been unaffected by the Crusades at the time. But he remembered enough about them to create a poem in which he compared his kid to a younger Salahuddin Ayyubi (Saladin). These can be lone instances or they might reflect bigger tendencies. Before accepting a historical theory that runs the risk of portraying Muslims as uninquisitive and prone to harboring unjustified grievances, we should ascertain the truth.